Fifty years ago, drunk on aluminum big-block V-8 racing victories, GM hoped to share its Can-Am, Trans-Am, IMSA, and NHRA success with faithful Corvette customers. A limited-production version of the already formidable L88 427 was prepared for the 1969 model year, but only two ZL1 Corvettes were ultimately delivered with the exotic alloy block that distinguished that fabled option code.

For the next model year, RPO LT2 would have consisted of the all-aluminum big-block as the soul mate to the 350-cubic-inch, 370-horsepower LT-1 small-block. Alas, a desire among GM management to prune engines from the company’s burgeoning powertrain lineup (a process known at the time as “de-proliferation”) raised its head and the LT2 was canceled, resulting in this option code slumbering for decades in obscurity.

Fortunately, GM is good at remembering its past by reprising special RPO codes. After bowing out in ’72, the LT1 reappeared (now sans hyphen) for the 1992-1997 model years, and a Gen V edition recently finished its sixth production year under Camaro SS, base Corvette Stingray, and Grand Sport hoods. The great news for 2020 is that the C8’s one and only (thus far) engine is an LT2 that embodies several remarkable engineering strides.

Though based on the 2014-19 LT1, the C8’s LT2 features enough incremental upgrades to boost output by 35-40 horsepower. Its appearance was a focus of designers’ efforts as well.

To keep Corvette’s base price from topping $60,000, powertrain engineers retained the one small-block V-8 feature crucial to its affordability: a simple-but-effective pushrod, two-valves-per-cylinder valvetrain. In fact, the direct-injection cylinder heads developed for the LT1 carry over to the LT2 intact. In the interests of low weight and compact dimensions, the 4.40-inch bore center spacing created for the original 1955 small-block is present and accounted for, as well as the 103.25mm bore and 92mm stroke dimensions that yield 6.2 liters of displacement.

In every other respect, the LT2 is a clean-sheet design with a fresh block and new intake and exhaust systems benefiting from advanced simulation and development technologies.

Cylinder Block

The new aluminum block has cast-iron bore liners for longevity, with four-bolt, nodular-iron main-bearing caps to secure the crankshaft. The block’s flanks incorporate pads for mounting the engine to the Corvette’s chassis, ignition-coil attachment points and appropriate stiffening ribs. As before, there are oil squirters to rid excess heat from the bottom sides of the pistons.

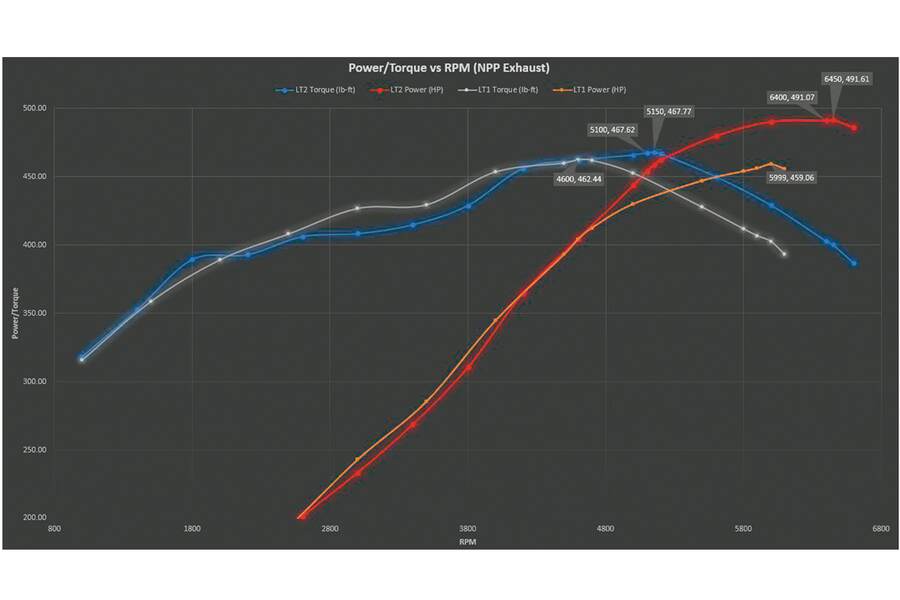

Graph compares the power and torque curves of these two Corvette small-blocks. Note the dramatic improvements logged by the LT2 above 4,800 rpm.

The most interesting new feature of the LT2 is a standard dry-sump lubricating system with a molded-plastic storage reservoir bolted directly to left-front corner of the block. This not only saves weight and space, it also eliminates the flow losses and possible leaks associated with external oil lines.

To reduce the C8’s chances of starving for oil during flat-out race track use, powertrain engineers went beyond closed-course durability tests by running the LT2 flat out on a tilting dynamometer, replicating loading up to 1.2g in every direction. One discovery was that up to three quarts of oil could be trapped in the cylinder block with the previous, external dry-sump system, raising the likelihood of momentary oil starvation.

To remedy that situation, engineers led by small-block chief Jordan Lee donned their thinking caps and came up with a novel solution. To expedite the return of oil from the cylinder heads and hydraulic lifter bores, they sealed the floor of the block’s valley and fitted a scavenge pump driven by the camshaft in that location. There’s a molded plastic scraper in close proximity to the crankshaft throws, and two crank-driven scavenge pumps in the shallow aluminum oil pan.

Upswept, racecar-style exhaust headers look great, perform even better.

These changes accomplished three ends: Only one quart of oil is in use at any given time, even during harsh running conditions; windage losses and oil frothing by the spinning crank are minimized; and the required supply of synthetic oil has been reduced from 9.7 to 7.5 quarts, saving weight and the reducing the cost of an oil change.

Clearly proud of the new dry-sump system, engineer Lee points out that the LT2’s clever “dry” valley arrangement is without precedent in the engine-design realm. Finally, to minimize parasitic losses, the oil-pressure pump is a two-stage design that delivers maximum output only above 5,500 rpm.

The beauty of any dry-sump arrangement is that it permits lowering both the engine’s mounting location and the car’s center-of-gravity height. To squeeze the most benefit from this opportunity, the LT2’s crankshaft centerline height is actually below the level of the transaxle’s half-shaft (output) axis.

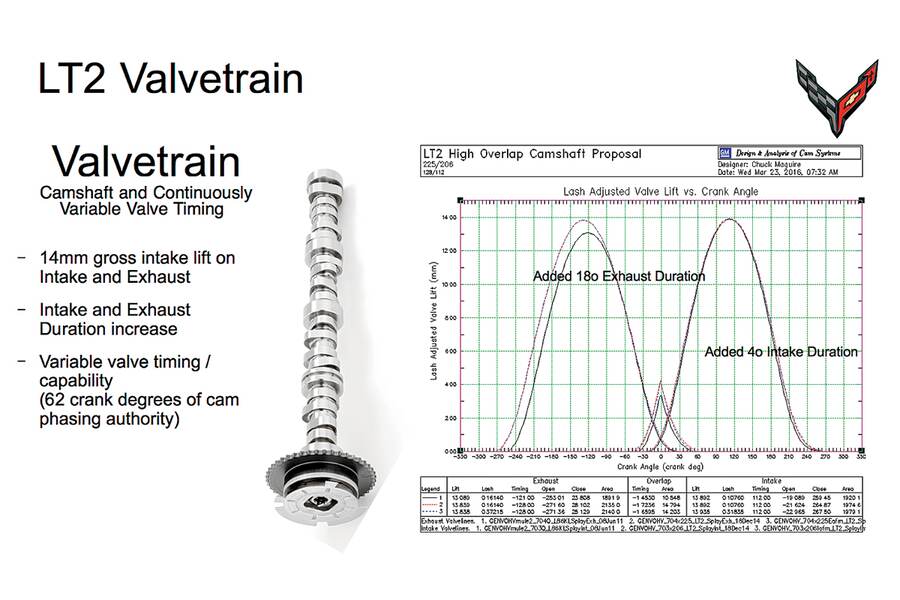

Variable valve timing ensures that the new engine offers optimum output and efficiency under all operating conditions.

Crankshaft

The LT2’s forged crank is made from a higher-strength S38 alloy material and equipped with a longer nose to drive three of the four oil pumps. The front damper has an aluminum hub and a steel inertia ring with a ribbed outer surface to drive accessory equipment. The small-diameter rear damper connects the engine to the transaxle, diminishing vibration from the engine’s output-torque variations that occur during the transition from the eight- to four-cylinder operating mode.

Induction System

Shifting the engine behind the driver eliminated concerns about the height of its intake manifold. With at least three inches more vertical space available, LT2 designers fed the beast ample air via a rear-mounted 87mm throttle body attached to a shell-molded, nylon-reinforced plastic intake manifold featuring eight 210mm-long runners. To create the intake, four moldings are bonded together using the heat of a friction-welding process generated by vibrating the mating parts.

While the resulting component is light and functional, it’s not very attractive, necessitating an engine cover—also molded plastic—contributed by Corvette designer Tom Peters. This extra step reflects the design team’s stated goal of making the car’s newly visible powerplant as attractive as the rest of the car. (And if the look isn’t for you, fear not: Chevy’s service-parts arm will sell its own, more highly stylized cover, and aftermarket companies are sure to offer their own renditions.)

The benefits of the LT2’s burnished design will be most evident on the road, where the 495-hp small-block is said to enable 0-60 times of less than three seconds.

Exhaust System

The upswept four-into-one, stainless-steel headers are both highly functional and far more pleasing to the eye than conventional iron or steel manifolds. Tapered collectors dump exhaust into round, closely coupled catalytic converters.

Valvetrain

To take full advantage of the less restrictive intake and exhaust systems, LT2 engineers increased the maximum exhaust valve lift from 13.5mm (the LT1 measurement) to 14mm. Intake lift remains at 14mm. Exhaust duration is 18 degrees greater, while intake duration is 4 degrees longer. While there are minor output losses between 2,800 and 4,500 rpm, compared with the LT1, peak power swells to 490/495 horsepower (without/with the performance exhaust system) at 6,450 rpm. Peak torque, meanwhile, rises to 465/470 lb-ft at 5,150 rpm.

With the throttle down, the eight closely spaced ratios in the new dual-clutch automatic expedite the trip to the LT2’s 6,600-rpm redline. And while the legendary ZL1 is said to have produced somewhere in the neighborhood of 560 horsepower, it’s important to remember that such ratings were calculated using the permissive “gross” testing regime typical at that time. Today’s net ratings are considerably more scientific, and Lee and company are sticklers for accuracy. If anything, the LT2’s cited 490/495 figures are on the conservative side.

As for the basic cylinder heads themselves, they are essentially unchanged from the LT1 design. They’re topped with attractive Edge Red Metallic valve covers, another reflection of the designer team’s newfound appreciation for engine-bay aesthetics.

Electrical Architecture

The 2020 Corvette is one of GM’s first vehicles to benefit from a new “Global B” electrical architecture tying all of the car’s electronic control modules together on a single high-speed party line. This system is not only capable of quickly handling the ever denser data flow typical of today’s cars and trucks, it will also deliver software upgrades wirelessly.

In the interests of maximum fuel economy and cruising poise, the LT2, like its predecessor, will use only half its cylinders at times. Intake- and exhaust-valve timing can be shifted by up to 62 degrees via the camshaft’s phase-changing drive system.

Manufacturing

GM’s Tonawanda, New York, plant, the home of the small block V-8 since 1955, is slated to build around 170 LT2s per day for Corvette use.

The Verdict

Those who scorn the LT2’s simplistic valvetrain design fail to recognize the value of the persistent polishing lavished on this gemstone. Lee and company, some of the shrewdest engine developers in the world, never wander down technological blind alleys. Ultimately, what matters most is the performance and driving satisfaction Corvette is able to deliver at a reasonable cost. Judged by that standard, there’s no doubt that the LT2 small-block is ready and willing to fulfill its mid-engine assignment.