One early morning in May 2016, the serenity of the undulating hills and vast expanses of picturesque woodland at GM’s Milford Proving Ground was fractured by the rhythmic thunder of an ultra-powerful Chevrolet V-8. Alex MacDonald, who was then Lead Development Engineer for Corvette and is now Vehicle Performance Manager for Chevrolet Performance Cars, strapped on a C7 ZR1 and eased it onto the Milford Road Course (MRC) for its initial shakedown. MRC is a 2.9-mile, 18-turn circuit that includes some of the most demanding features found on racetracks around the world.

As is always the case, the primary purpose of that initial test drive was to ensure that the car, an early integration vehicle hand-built at GM’s prototype shop in southeast Michigan, had no glaring problems. “The first test,” explains MacDonald, “is to make sure the fluids all stay in the car, and the wheels stay bolted on, and everything is basically functional and safe for the rest of the testing to begin. So you drive the car quite conservatively.”

Even when driven conservatively, however, the savage performance capability inherent in the still-nascent ZR1 made itself known. “The funny thing about that test,” recounts MacDonald, “is that I got onto the MRC’s front straight, taking a fairly conservative line because it was our very first lap with the car, and when I got to the start-finish line the speedometer said 168 mph. I radioed in and said, ‘I think we’ve got an issue with the speedometer.’ It seemed to be off by a pretty good margin, because that’s about 10 mph faster than we’d see with a Z06. After I finished the session, we pulled up the GPS data, and sure enough, lap one…was 168 mph. So we knew right at that moment that it was a special car.”

That the new ZR1 was so fast right out of the gate illustrates what can be accomplished when engineers with deep experience, innate talent and the most sophisticated computer-driven design and simulation tools available accept the challenge to create the latest in a storied line of “King of the Hill” Corvettes. But at the same time, the fact that MacDonald’s blistering first lap was only the beginning of a two-year-long journey that would transform ZR1 into an apex predator extraordinaire proves just how invaluable track tuning is.

“The role of track testing versus simulation is an interesting [question] right now, because a lot of things are moving to simulation environments,” explains MacDonald. “You have to consider the phase of the program and what tools are appropriate. So, early on in a program when we’re trying to decide how much power the car needs, [whether it’s] better to have more power or less weight, more aerodynamics or less drag—basically, where the compromises need to be made—we have really good simulation tools that help us. What we don’t have yet is really good simulation tools that let us do the fine tuning—or at this point, even the gross tuning. We can build a car that we know is capable of meeting our performance goals, but we can’t really get it any further than that without physically being at the track.

“Having the MRC on site for the past 10 years has brought a deeper understanding to the organization of how much information you can get quickly at a racetrack, and it’s changed the whole way we do business. It used to be that we thought we could do most of our testing on a regular proving ground and then go check the car on a track. It turns out [that] often, in a performance car, [it’s] much more efficient to go to the track early. We squeeze months of regular testing out of just a few hours on a racetrack, just based on the demands we put on the car. So, between those two things—the fact that simulation isn’t really up to the point where we can do much of the performance development, and the fact that we have ingrained the good-quality data you can get from a racetrack into our engineering lifestyle—track testing is a natural and required part of a program like Corvette.”

Hitting the Track

As with all of GM’s performance vehicles, the bulk of initial ZR1 track tuning was done at MRC. The logistics of testing at Milford are obviously helpful, but beyond that, everything from the layout to the track surface is hugely beneficial. It’s important to remember that, unlike the many other facilities GM and other car companies use for testing, MRC was designed from the beginning to serve as a development track.

The Corvette team spent a little over six months at MRC, pushing their early-integration vehicles up to and beyond their limits to find and then solve problems, and doing the initial tuning needed. After they were confident that all of the developmental heavy lifting was done, and the car was developed to within 80 percent of its potential, they moved their track testing to Virginia International Raceway (VIR), a beautiful, natural-terrain road course that has served as the Corvette development team’s “home away from home” for several generations.

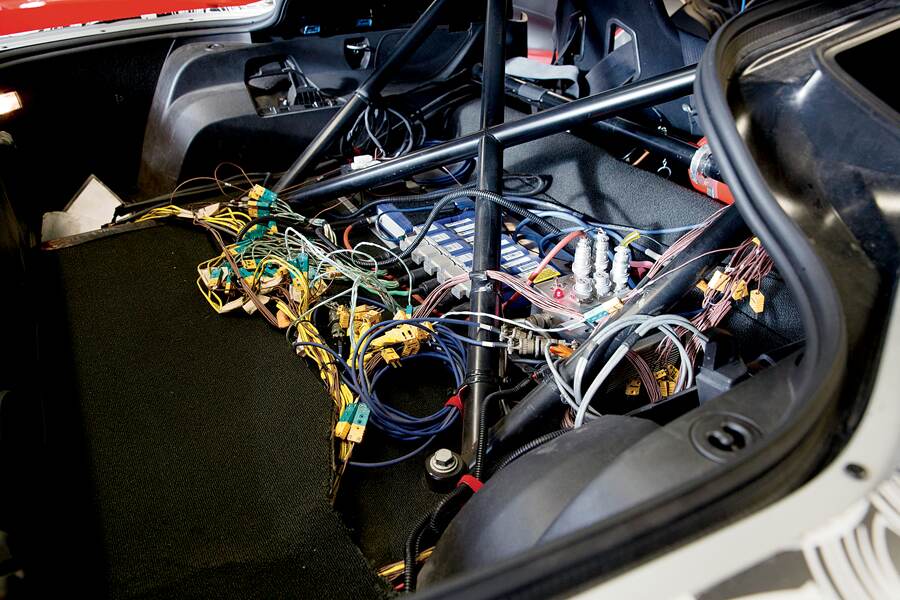

Moving the whole operation to VIR (as well as the other tracks where the team ran ZR1s, including California’s Willow Springs and Laguna Seca) was a major logistical undertaking. All of the test cars, tires, parts and tools needed to be transported to the site. Then, a small army of people needed to be brought in. “We’ll typically have 30 to 40 people at the track,” explains MacDonald, “and they can be divided into four groups, starting with the drivers. I call them ‘independent contractors’ because they’re each responsible for a chunk of the car, and they’ve got a certain amount of vehicles and resources that they can use to get their work done at the track. On my team they’re all engineers and all certified by GM to drive on track. They’re the people integrating the whole car together.

“Then, we’ve got a team of GM support engineers, including people from powertrain, brakes, driveline, cooling and so on. These engineers are there to support the test plan that we’ve established in order to make sure the car performs well. Then, we’ve got a group of suppliers supporting calibrations,, and they need to be at the track with us. This group includes Bosch, for ABS, [as well as] Michelin, our transmission suppliers and several others. And, of course, we’ve got a team of technicians who keep the cars running and do all the component changes that are needed to do the tuning. They replace tires and brakes, and do all kinds of magic to keep the cars running the whole time.”

Because virtually all of the reliability issues and initial tuning were already done at MRC, the team could focus almost exclusively on fine tuning once they got to VIR. “We know that track really well, so there’s not much of a learning curve to determine what a car needs there,” MacDonald says. “So the trips to VIR are generally the ones where we get to exercise the car at a track where we have a lot of competitive benchmarking and where we’re doing more fine tuning. We’re generally not ‘turning big knobs,’ and we certainly expect that the car is going to run the whole time, so we’re swapping stabilizer bars and springs, and testing other basic tuning components on the car.”

After four months of track testing at VIR, Willow Springs and Laguna Seca, 95 percent of ZR1’s fine tuning was dialed in. But to help squeeze out those last remaining bits of performance, the Corvette development team made the first of two trips to the Nürburgring. This circuit, extending for some 12.9 miles through the Eifel forests in western Germany, includes 73 turns and more than 1,000 feet of elevation change. Because of the difficulty and danger posed by the legendary road course, only the most skilled and courageous drivers can push a car to its limits here. But when they do, the rewards are plentiful.

“We do make an effort to tune everything at the Nürburgring,” explains MacDonald, “because it’s such a unique environment. The track surface is not something you would see anywhere in the U.S., for good and bad. If we tuned the car entirely on the Nürburgring and never looked at VIR or Road Atlanta, we’d have a mess. It wouldn’t be a good-handling car at all. But vice versa, if we only focused on the smooth, spec-width, proper racetracks here and didn’t look at the crazy, undulating pavement at the ‘Ring, we would also miss a lot. So it’s a vital component [allowing] us to fill in a lot of gaps.”

Running a record-setting lap at the Nürburgring is something all performance-car manufacturers strive for, but it’s incredibly difficult to do that, especially for non-German companies. “I think the interesting thing about the Nürburgring is how difficult it is for an American manufacturer to do well there. If you think about the way we operate with VIR, for instance, [when] we had to go do a validation test, we called up and had track time reserved for the next week. We jumped in our cars and drove down, tested for five days and came back. That’s the way a German manufacturer can operate with the Nürburgring. With us, we have to pick a date six months ahead of time. If we show up and it’s raining or it’s cold or it’s 90 degrees or any number of conditions you might expect in that part of Germany, we’re sunk. We just wait [until] the next year and we try again. So it’s a very frustrating place to do development work because you really are stuck with the conditions you’re given, and that can make a program go through a dry spell of many years without a lap time [there]. We still get development work done, but it takes all the right things to line up for an optimum lap time. And if you can’t pick a day when [those factors] are going to line up, you’re just at the mercy of luck when you plan your trip. We get a ton of data there that we don’t get elsewhere. It’s unlike any other track in the world, but getting a lap time…out of that place is really a pretty rare event.”

Final Tuning

All of the ZR1 calibration was completed toward the end of 2016, allowing the Corvette development team to focus on the next and final phase of their work, called validation. As the name implies, validation consists of a variety of tests designed to verify that the car meets or exceeds a long list of performance, safety, drivability and durability requirements.

One of the most important things that distinguishes GM’s ultra-high-performance cars from some of their competitors is the company’s self-imposed requirement that every car it produces, including its flagship ZR1, must meet all of the same usability and durability requirements as every other car it produces. That means ZR1 underwent the same cold-weather torture processes at GM’s facilities in Kapuskasing, Canada and Kinross, Michigan as its more mundane brethren, and had to pass all the same snow and ice validation tests. “It even had to ford a 12-inch-deep water trough, which is something you wouldn’t necessarily expect from a car in this performance category,” points out MacDonald.

Every GM car has some level of track capability on a continuum the company uses, and predictably ZR1 must meet the most extreme level, called 3C. As a level 3C car, ZR1 is certified to do continuous lapping on a road course near the limits of its ultimate performance. To earn level 3C certification, the car had to successfully complete a 24-hour validation test with no failures of any kind, which it did at VIR in January 2018.

“During the 24-hour validation test, we’re not changing anything on the car, we’re just putting hours on it,” explains MacDonald. “We’re really just focused on driving the car we’ve made rather than tuning, and an amazing thing about validation is that our lap times will improve by two to three seconds compared with lap times during our calibration work. When you free up parts of your brain that are thinking about engineering, and you let them just think about the car, that’s when the magic comes out in terms of ultimate speed.”

And, in fact, the magic did come out during that span. “We were at VIR for five days,” recounts MacDonald, “and during the second day press started to come out on the Ford GT. First, there was the Car and Driver lap time, which we know is between three and five seconds off the car’s ultimate potential. That’s just the delta you have for the magazine writer. It’s pretty consistent across every car we’ve seen, and that’s not a knock on them. It’s good work on their part; it’s just that they drive a lot of different cars so they don’t have a chance to soak in anything. But if we put our delta on that, we start to think, Man, that’s really not all that fast, and then Ford’s driver, Billy Johnson, tweeted his lap time and said, ‘I guess the news is out, it’s a new record at VIR.’”

During routine testing on VIR’s Grand Course layout, Ford development driver and pro racer Johnson had clicked off a blistering time of 2:38.62. That easily eclipsed the previous production-car record of 2:40.02, held by a Viper ACR, and obliterated Car and Driver’s best lap of 2:43.0, which was the fastest time the magazine had ever recorded for a production car at the time.

“When this news reached us,” remembers MacDonald, “we were running the full course, not the Grand Course that the record is typically kept for. But we were looking at our full-course time and thought we could go faster than the GT if we were on the Grand Course. So, the next morning we asked Kevin at VIR if we could just switch over to the Grand the following day, because for the test we were doing it didn’t matter what track we were on. He switched the course over for us. Jim Mero, who has been a Corvette development engineer and our cornerstone at the track for many, many years, got a 2:37.2 lap during his second session. We had a couple of timing systems running, so we were sure it wasn’t a mistake.“After coming in for gas, Jim, who has set numerous lap records with Corvettes starting with the C5, went back out and immediately ran another 2:37.2. So, two of them back-to-back just ‘fell out of’ the work we were doing. Like I said, we were in that validation phase where we were driving the car a lot, so it’s not a surprise that we got that kind of performance, but it really was just on a whim. We were watching the media stuff come out of Ford, and we thought we could run faster just as part of our normal testing and we did, so it was a fun week!”

Anyone fortunate enough to own a new ZR1 owes a debt of gratitude to Alex MacDonald; Matt Satchell, the new Lead Development Engineer for Corvette as of June 2017; Jim Mero and the entire Corvette development team. Without their dedication and hard work at numerous tracks around the U.S. and at Germany’s Nürburgring, Chevy’s C7 ZR1 would still be a great car, but it probably wouldn’t be an apex predator among the world’s top performers.