All the way back in 1965, anyone with about $4,500 to spare could buy an L78-optioned Corvette and, with it, rule the streets. The formula was simple: a Mark IV big-block Chevrolet engine displacing 396 cubic inches and delivering 425 horsepower in a car that weighed about 3,200 pounds. This engine was a direct descendant of the fabled 427 Mark IIS “Mystery Motor” that scorched a path to NASCAR victory circles in 1963 in the hands of Johnny Rutherford, Junior Johnson, Rex White and others. Like the small-block Chevrolet introduced in 1955, it set the racing world on fire and upended the auto industry with an unbeatable combination of high power and torque, low mass, excellent reliability and low manufacturing cost.

The Corvette’s 396 big-block lineage can be traced back to Chevrolet’s first large-displacement V-8. Called the W-series or Mark I engine, it was introduced in 1958 with a displacement of 348 cubic inches, and later enlarged to 409 cubes. The W engines were commercially successful, most notably in Impala Super Sports, as immortalized by the Beach Boys in their 1962 hit song “409.” They were also quite successful in competition, beginning with Junior Johnson’s 1960 Daytona 500 victory in a 348-powered ’59 Chevy.

Though they were winners on and off the track, the W-series powerplants did have some weaknesses and limitations that ultimately led to their demise. They were relatively heavy, tended to run somewhat hot and couldn’t be enlarged beyond about seven liters (roughly 427 cubic inches) without extensive changes. Moreover, their exterior dimensions made it impractical to install them into Corvettes or the small and intermediate cars coming down the pipeline, such as Chevy IIs and Camaros. But perhaps most concerning of all, the Chevrolet engineering team eventually hit a wall regarding the W engine’s power output because of design limitations. The combustion chamber was partially in the block, and the top of the block was not square to the centerline of the bore or the top of the piston. This convoluted arrangement restricted important considerations, such as combustion characteristics, valve size and placement, and bore diameter.

The way around these inherent shortcomings was a new, clean-sheet design. In mid-1962, shortly after Bunkie Knudsen moved from Pontiac to take the helm as general manager of Chevrolet, he gave Chevy chief engineer Harry Barr the go-ahead to design a replacement for the 409 race engine. The team working under Barr, led by brilliant engineer Dick Keinath, went to work in July 1962 to design an all-new engine, which would be called the Mark II.

Aside from a common bore spacing of 4.84-inches, the Mark II engine shared nothing with its predecessor. The new cylinder case was completely square, with the block’s deck surface at 90 degrees to the crank centerline, and the pistons square to the deck surface. The cylinder heads were completely new as well, with integral combustion chambers and canted valves, which gave rise to the nickname “porcupine” heads. The machining for the valves, as well as all of the related components, was particularly challenging in the era before computer-aided design and tools, but the new head’s superior airflow characteristics were well worth the investment of time and expertise.

The Mark IIS (“S” because it was a 427-ci stroked version of the 409 cid Mark II) made its debut at Daytona in 1963. Unknown to most people, however, the engine’s maiden appearance was not in the Chevy stock cars contesting the Daytona 500. Instead, their very first race was in Daytona’s American Challenge Cup, a 250-mile event that included GT cars. Two of Mickey Thompson’s Z06 Corvettes entered in that race had been retrofitted with Mark IIS 427 engines by Smokey Yunick. They were the fastest cars in the field, with Junior Johnson driving one to first and Rex White driving the other to second in the event’s qualifying race. But poor handling and issues resulting from heavy rain relegated them to Third and 13th in the final standings.

Six days after the American Challenge Cup, Mark IIS–powered Impalas swept the Daytona 500 qualifying races. Johnson won the first 100-mile qualifier in a Ray Fox–entered car at a record-setting average speed of 164.083 mph, while Johnny Rutherford won the second qualifier with an average speed of 162.969 mph. The Mark IIS Impalas were the fastest cars in the Daytona 500, with three of the four leading at some point, but all suffered mechanical problems and bad luck that put them well back at the end.

Owing to GM’s publicly stated policy of not racing, which dated back to the Automobile Manufacturers Association ban of 1957, Chevrolet bent over backwards to hide its involvement with the Corvettes and Impalas competing at Daytona. This led the press to dub the engine powering these cars the “Mystery Motor.” Though the moniker survives to this day, the new engine didn’t remain a mystery for long. The cars were so far ahead of their competition (the Impalas were running a full 10 mph faster around Daytona) that everyone wanted to know what was lurking under their hoods, and in short order the existence of an all-new engine was revealed. That, in turn, led to an edict from GM’s top management stating that anyone caught participating in this covert race-engine program would be fired immediately. And just like that, the Mystery Motor was history.

The cessation of Mark IIS production did not, however, mean the end of the big-block engine at Chevrolet, which had planned to put a street version of the mill into passenger cars and trucks from the very beginning. In fact, the termination of the race program allowed Keinath and some of the other engineers responsible for the Mark IIS to devote all of their attention to designing and developing a new, production-ready rendition of the engine.

They began experimenting with a different bore center to allow for a greater bore-to-stroke ratio, creating what logically came to be known as the Mark III. This powerplant proved infeasible for a number of reasons, so they went back to the proven 4.84-inch spacing, and the resulting engine, called the Mark IV, ultimately became the production version. It differed from the Mark IIS in a lot of important ways, including its revised intake and exhaust manifolds, additional and repositioned bolt holes, slightly different valve angles, higher tin content in the block and cylinder-head material, relocated head ports, and smaller-bore/longer-stroke configuration delivering the same 427 cubes.

Interestingly, Keinath and his colleagues would have preferred to stick with the Mark IIS engine’s 4.3125-inch bore and 3.650-inch stroke, but the Tonawanda engine foundry insisted on a smaller bore to allow more leeway for “core shift,” an anomaly in the casting process that causes the cylinder walls to be thicker in some areas and thinner in others. That led to the Mark IV having a bore of 4.250 inches, which in turn demanded a stroke of 3.750 inches to arrive at 427 ci.

The engineers’ bore-vs.-stroke wishes proved moot for 1965 because the Mark IV was introduced at a displacement of 396 rather than 427 cubes. This was because of GM’s self-inflicted prohibition against selling intermediate-or-smaller cars equipped with engines larger than 400 ci. To slip below that number, Chevy used a 4.094-inch bore and a 3.76-inch stroke, and for Corvette the engine was stuffed full of high-performance parts. These included 11.0:1-compression, impact-extruded aluminum pistons; a forged crankshaft and connecting rods; four-bolt main bearing caps; an aggressive solid-lifter camshaft; a high-rise aluminum intake manifold; square-port cylinder heads and a 750-cfm Holley four-barrel carburetor. All of this goodness added up to 425 hp at 6,400 rpm and 415 lb-ft of torque at 4,000 rpm.

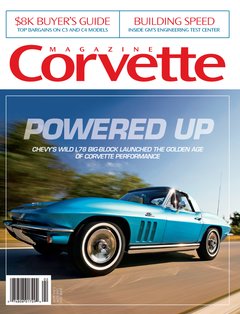

Our feature car is one of 2,157 ’65 Corvettes that left the St. Louis factory with the new big-block. At a cost of $292.70, the L78 option was $245.30 less than the next-most powerful engine, a 375-horsepower fuel-injected 327, making it something of a performance bargain. In addition to the monster engine, L78 Corvettes got a larger front anti-sway bar; a 9/16-inch rear sway bar; stiffer front springs; a larger, copper-core radiator; a larger cooling fan; stronger steel half-shafts using bolt-secured caps and a different hood with a vented “power dome.”

After the person who ordered our stunning Nassau Blue roadster refused to complete the transaction (reportedly because of difficulties obtaining or paying for insurance), it sat in G. Maxton Chevrolet’s showroom in Angola, Indiana, though not for long. Jim Griem, who happened to live a few miles from the dealer, was driving by one day in his six-month-old ’64 GTO when the Corvette caught his eye. A deal that included trading in the almost-new GTO was struck, and Griem took the big-block Corvette home on July 5, 1965. He loved the car and used it for everything, including towing a matching Nassau Blue boat to and from his local lake. When he and his fiancée Barbara tied the knot in November of ’65, they drove off in the car, complete with a giant “Just Married” sign on the rear deck and tin cans dragging behind. When they bought a second car, Mrs. Griem drove the Corvette more often than not and grew very attached to it.

The Griems reluctantly sold the still-like-new Corvette to a man in Indianapolis in 1977 in order to buy a station wagon for their growing family. To this day, Mrs. Griem still remembers crying as the new owner drove away. The changed hands again before going to fourth owner Lee Roy Neitzel in Kansas in 1982. Neitzel replaced the original wheels and hubcaps with reproduction knock-offs, and enjoyed driving and showing the car for several years. He was involved with the NCRS and earned a Top Flight award with the car at an NCRS Rocky Mountain Chapter event before selling it to a Corvette dealer on the West Coast.

The fifth owner of the car, Lenny Werner, is from Connecticut but happened to be in California on a business trip when he made a detour to the dealership and saw it in the showroom. After having it shipped back east, he drove the Corvette about 200 miles before starting some restoration work. The only things that needed attention were the brakes and radiator, both of which leaked slightly, but he decided to go well beyond that. He got as far as partially disassembling the car, getting a lot of the original fasteners re-plated, gathering a significant array of N.O.S. parts and doing a few other things before putting the project aside. For more than 20 years, the car remained in virtually the same state—up on jack stands, partially disassembled, with all of its parts meticulously organized and labeled.

Current owner Rob O’Neill already had a 396 Corvette and wasn’t looking for another one, especially not a convertible. He also had a 427/450-hp ’66 [historical note: this early output figure for the L72 was later reduced to 425], and his search for some needed parts to complete that car is what led him to our feature car. “I needed two wiper grilles for a very early ’66 that I’d recently purchased, [so I] responded to an Internet auction site listing for grilles,” O’Neill explains. “While speaking with the seller, I asked what else he had for sale, and he rattled off some parts and then mentioned that he was gathering some pictures of a 1965 396 he was thinking of selling.”

When O’Neill visited Werner to pick up the grilles, he was shown recent photos of the 396 roadster and was shocked by what he saw. “He told me the car had been in his barn for over 20 years and was completely apart. I kind of assumed he was a farmer and there were cows sleeping next to it. But the barn was more like a shrine, or a museum that you could sit in, have a beverage and imagine how cool the Corvette would be if it was completed.”

O’Neill stayed in touch with Werner, and a few months later, when he happened to be back in Connecticut, he stopped by to see the car in person. “When I arrived we headed down to the barn,” he recalls. “There sat the roadster with the original 396 next to it [and] all the parts he removed, carefully rebuilt, painted and plated. [They were] labeled and wrapped, in containers, awaiting the day he would start putting it back together.

“He started to unwrap some of the parts, and I told him to stop and put the parts back in the containers because I had seen enough,” O’Neill continues. “Four hours later we were heading back to Long Island with the car. I just could not believe it, considering it all started with my needing wiper grilles.”

O’Neill wasted no time in getting to work on his new acquisition. He finished disassembling it and sent the chassis and suspension parts to Action Powder Coating in Farmingdale, New York. The engine, meanwhile, went to Glen Briglio at B&B Machine in Oceanside. The original carpet, door panels and dash pads were cleaned up, and Al Knoch Interiors recovered the seats. Roque Pimentel expertly restored all of the car’s stainless trim, and A&B Interiors in Baldwin installed a correct new soft top.

Along the way, O’Neill traced the ownership history of the car and was delighted to discover that the fourth owner, Lee Roy Neitzel, still had the original wheels and hubcaps that he took off in 1982. so those parts went back on the car. With help from his wife and three daughters, O’Neill reassembled the Corvette himself and completed it only four hours before it was scheduled to leave for the Bloomington Corvette event in Indiana. Although this was the first time O’Neill had entered a Corvette in a show, his efforts paid off with a coveted Bloomington Gold Certification.

Even more gratifying than earning the award, O’Neill had an opportunity to visit with the car’s original owners, Jim and Barbara Griem, while he was in Indiana. “I was able to find [them] beforehand because their name and address are on the original Protect-O-Plate that’s still with the car,” he says. “When we were a half-mile away, I unloaded the Corvette and drove it up their driveway. They were in tears!

“I took Jim for a ride and…we talked about the good old days for over three hours. For me, it was a privilege to meet such beautiful people, and as happens so often, it was a Corvette that brought us together. This is yet another reason why I love the Corvette hobby so much, and why this particular car is so special to us.”