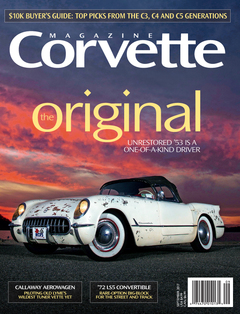

With pageantry befitting a Hollywood premier, and all the showmanship of a Broadway production, the grand ballroom doors of Manhattan’s Waldorf-Astoria Hotel swung open on January 17 to kick off GM’s 1953 Motorama. The undisputed star of the show in New York—as in subsequent showings in Miami, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Boston—was a gleaming, white, fiberglass-bodied sports car called Corvette.

Chevrolet’s sporty two-seater was the brainchild of Harley J. Earl, the godfather of automotive design who led GM’s Art and Color Section (later called GM Styling) for more than three decades. The genesis of the idea likely stems from Earl’s own fascination with cutting-edge styling and high-performance cars, as well as his sons’ interest in post-WWII sports cars. The final motivator may well date to September 1951, when Earl brought his LeSabre “dream car” concept to Watkins Glen, then a hub for sports-car racing in the United States. While at the Glen, Earl got up close and personal with the best European sports cars of the era.

By the spring of 1952, a small group of GM engineers and stylists hand-picked by Earl had penned a sports-car design and created a full-size plaster model. Upper management, including GM President Harlow “Red” Curtice, Chevrolet General Manager Thomas H. Keating and Chevrolet chief engineer Edward Cole, all liked what they saw and gave their approval to transform the design into a functional dream car for the following year’s Motorama.

The prevailing story is that tremendous public reaction to the Motorama Corvette convinced GM to quickly put it into production, but that is not entirely accurate. The lead designer for the Motorama Corvette, tasked with transforming Earl’s ideas and rough sketches into a finished product, was a recent Cal Tech graduate named Bob McLean. McLean also happened to be an engineer, a fact not lost on Earl. It’s also no coincidence that the lead engineer assigned to work with McLean was Maurice Olley, head of Chevrolet’s Research and Development Department. Olley began his career at Rolls Royce in 1912 before joining Cadillac in 1930, so by 1952 he had amassed 40 years of diverse experience in engineering, designing and manufacturing. From the beginning, the fully functional Motorama show car was intended to be feasible for production, making it something of an anomaly among GM dream cars of the era.

Together, Earl, Keating and Cole were the driving force determined to put Corvette into production. But to do so they had to gain the approval of Harlow Curtice, and it was he who insisted upon waiting to gauge the public’s interest as the 1953 Motorama toured the country. Predictably, people were captivated by Chevrolet’s radically styled two-seater, and GM reportedly received more than 7,000 letters from prospective buyers. That was more than enough to overcome any remaining resistance within GM’s top ranks, and Curtice gave the go-ahead to enter Corvette into production immediately. But in reality, the car was already coalescing well before Curtice issued his approval.

In order to get the ’53s into customers’ hands as quickly as possible, a temporary assembly line was set up in a small customer delivery building on Van Slyke Avenue in Flint, Michigan. The very first production Corvette reached the end of that line on June 30, 1953. By December a total of 300 ’53 Corvettes had been completed. Each of the hand-built cars was painted Polo White with a Sportsman Red interior, and all were fully equipped with the nominally “optional” radio, heater, directional signals, windshield washers, courtesy lights and whitewall tires.

The ’53 Corvette’s chassis was similar in design to that of other GM cars, but modified with reinforcements to compensate for the absence of a structurally rigid steel body. Most of the front and rear suspension was sourced from Chevrolet’s passenger-car line, with a few changes and additions, such as a large front stabilizer bar, to accommodate Corvette’s diminutive size and low hood line. Similarly, brakes and steering, with a few tweaks, came from the Chevy parts bins.

The job of propulsion fell to Chevrolet’s venerable inline six-cylinder engine, coupled to a two-speed Powerglide automatic transmission. For use in Corvette, the six was modified with a high-compression cylinder head, a more-aggressive camshaft, triple Carter YF side-draft carburetors and dual exhaust. These changes boosted output from 115 to 150 horsepower, giving the low-slung sports car respectable, if not sizzling, performance.

The most innovative aspect of the whole car was its fiberglass body. Manmade plastics were not new in 1953—nitrocellulose, the first completely synthesized example, in fact dated back to 1856. However, the science of plastics was still relatively nascent, and its use in the mass manufacture of automobile bodies had not yet been attempted. But World War II accelerated advances in the field, and various companies, including Chevrolet, had been working on plastic body panels since the war ended. This led Olley and others to conclude that the technology was far enough along to utilize for Corvette. [See “GM Meets GRP,” elsewhere in this issue.] In fact, without the benefits of low tooling cost and short tooling time that fiberglass-reinforced plastic body panels offered, Corvette would definitely not have gone into production in 1953, and may not have gone into production at all.

Unrestored, Unrepentant

Today the exact number of surviving 1953s is not known, but it’s probable that only about 100 complete, or nearly complete, authentic examples still exist. Of these, our feature car, which happens to be serial #100, is likely to be the only one that is still driven on a regular basis. It is also one of the very few first-year Corvettes that remain largely unrestored.

The car rolled off the makeshift Flint assembly line in August 1953 and was trucked to Hoskins Chevrolet in Chicago. Chevrolet’s questionable marketing scheme for first-year Corvettes was to sell them to actors, business moguls and other “VIPs,” the better to raise the new model’s profile. This includes #100, which was sold to Cyrus Rowlett Smith, an aviation industry pioneer who was then president of American Airlines.

Today #100 is owned by New Yorker Gary Pasquaretto, who loves and appreciates everything about this rare car. Pasquaretto began working part time in his father’s Goodyear dealership at the age of 12, and it was this experience that first ignited his passion for performance cars. But it wasn’t until his older brother bought a new Corvette in 1978 that he developed a special reverence for the marque. “At the time, to me, that Corvette was the hottest car ever, and I knew one day I had to have one,” he tells us.

The desire to own a Corvette didn’t wane in the years that followed, but finances led Pasquaretto to keep putting off such a purchase in favor of other, less expensive sporty cars. He even went through a Mustang phase in the late 1980s. “I was particularly interested in ’64 Mustangs because I’m a ‘first year’-kind of a guy with most of the things I collect.”

In 1990 he finally took the plunge and bought a ’61 Corvette. “The reason I went for [that car] was because as I was born in October 1960, and that would have been the new car for sale at that time,” he explains. “It was red with white coves, a four-speed and a numbers-matching 283. At first I was very nervous heading down the road in it, but over time I got used to the feel of driving it and the attention it drew.”

Pasquaretto loved his ’61 but always kept his ear to the ground for a ’53. The problem, however, was that he wanted a car that was appropriate for frequent use, meaning one that was mechanically sound but not so nice that it was prohibitively expensive. “Most ’53s were far out of reach financially because they were trailers queens,” he says. “Or they were total wrecks…so I just waited on the sideline for a driver.”

The long wait finally yielded results in 2005, when noted six-cylinder-Corvette expert and ’53 collector Alan Blay turned Pasquaretto on to #100. “The car was for sale,” he explains, “but the seller was having trouble finding a buyer because it looked so rough. I wasn’t frightened by its appearance and made the purchase sight unseen.” When the car was delivered, Pasquaretto was thrilled to find that almost all of its original parts were intact and functional. Blay was equally excited, labeling it a “diamond in the rough” after a thorough inspection.

Because he intended to drive his new acquisition regularly, Pasquaretto made reliability a priority. In pursuit of that goal, he went through the entire brake system, starter motor, generator, horns, gas tank, carburetors, lights, radiator, heater, wiper motor, transmission and engine. Everything was cleaned, adjusted and, if necessary, rebuilt. So as to maintain the car’s incredible originality, the only parts he actually replaced were the brake-system seals. Finally, in the interest of safety, he installed vintage seat belts—which were not available from the factory until 1958—and radial tires. He did, however, make sure the radials had wide whitewalls to maintain a period-correct look.

As far as the appearance of the car is concerned, Pasquaretto initially planned to repaint the body, but has since reconsidered. “The more I drive the car, the more people see it and tell me to leave it alone,” he relates. “It seems almost every car on the road looks new and shiny, including most vintage Corvettes. When people see this thing…their reaction is like they just saw Babe Ruth at the gas station. They cannot imagine that something so rare still exists and…is being driven.”

Pasquaretto takes this incredible survivor for 20- to 30-mile drives about three times a month, year round, even in the dead of New York’s winters. He added a child seat after his son was born in 2012, and it’s safe to say the younger Pasquaretto has since had more “seat time” in a ’53 Corvette than almost anyone else on the planet.

“I think he really enjoys it,” Pasquaretto surmises, “because with today’s cars and their advanced climate control, no one ever has their windows down. Well, a ’53 Corvette doesn’t have windows; it has side curtains, and I leave them off eight months a year. So my son gets a big thrill with the noise and the wind while driving.

“In the winter, with the side curtains installed and the heater blowing, the car is nice and warm but a little drafty. So I use foam pipe insulation around the edges of the side curtains and convertible top, which works great.”

Looking ahead, Pasquaretto intends to simply keep doing what he’s been doing for the past dozen years, which is relishing every moment behind the wheel of the 100th Corvette built. “Many people say that owning things is OK, but having experiences is better. Having a 1953 on a trailer is fine for most, but having the experience driving this car out on the road is the best. It has given my son and me memories that are priceless.”